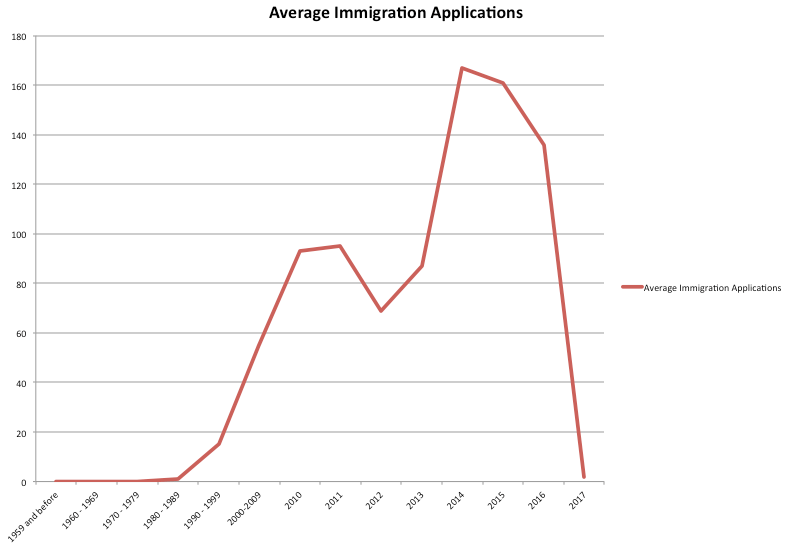

Our last blog post on the UDRP, breaking down losses in 2016, was quite popular, so we’re doing an update for cases in the first quarter of 2017.

Data set

The data was manually coded from the National Arbitration Forum (“NAF”) searchable case database with decision dates from January to March 2017. Our previous research found similar outcomes for World Intellectual Property Organization (“WIPO”) proceedings, so this update focuses solely on NAF decisions.

| Outcome | Cases | Percentage |

| Cancellation | 0 | 0% |

| Transfer | 342 | 92.7% |

| Denied | 27 | 7.3% |

| Total | 369 | 100% |

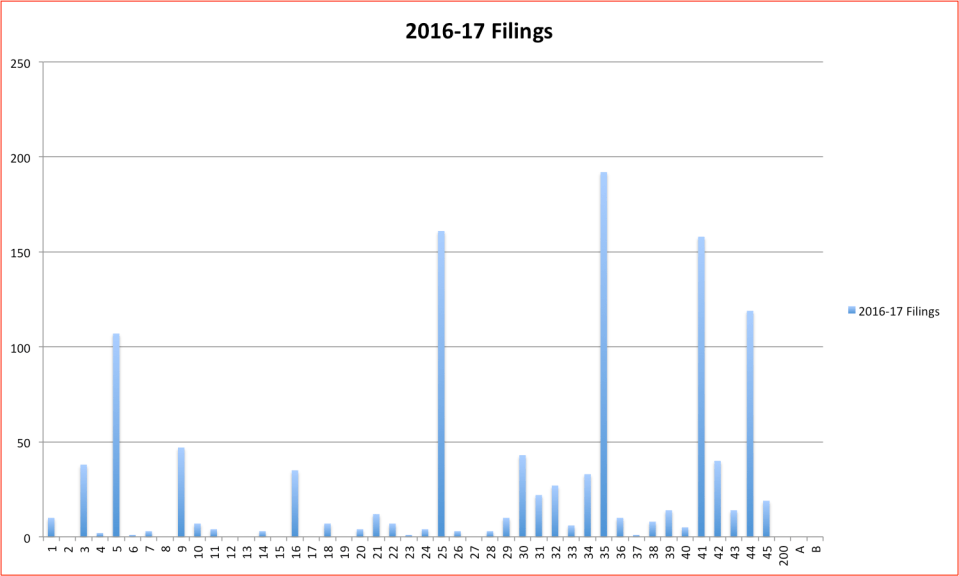

Trends

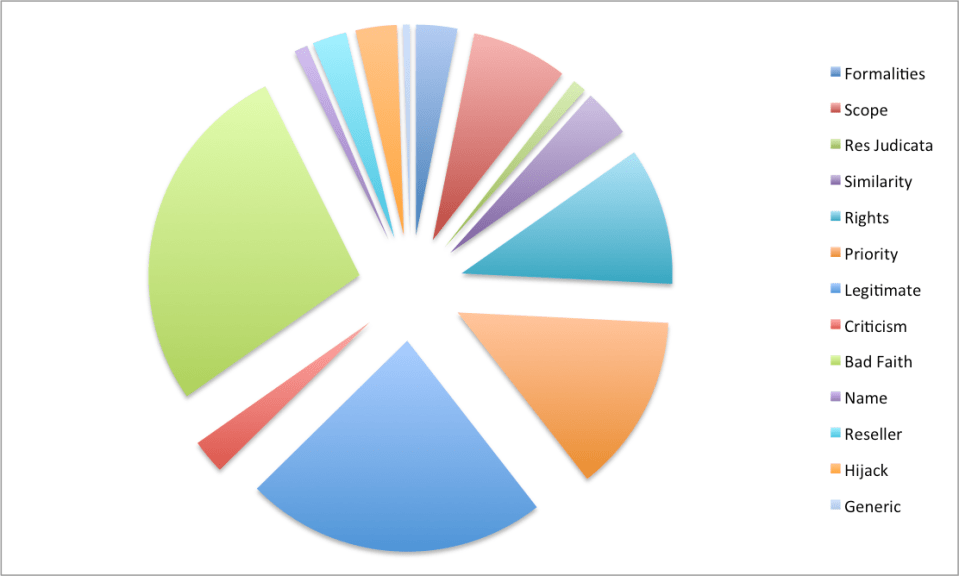

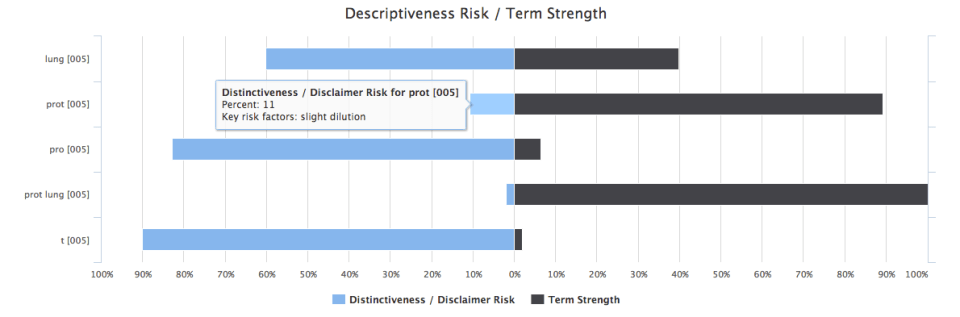

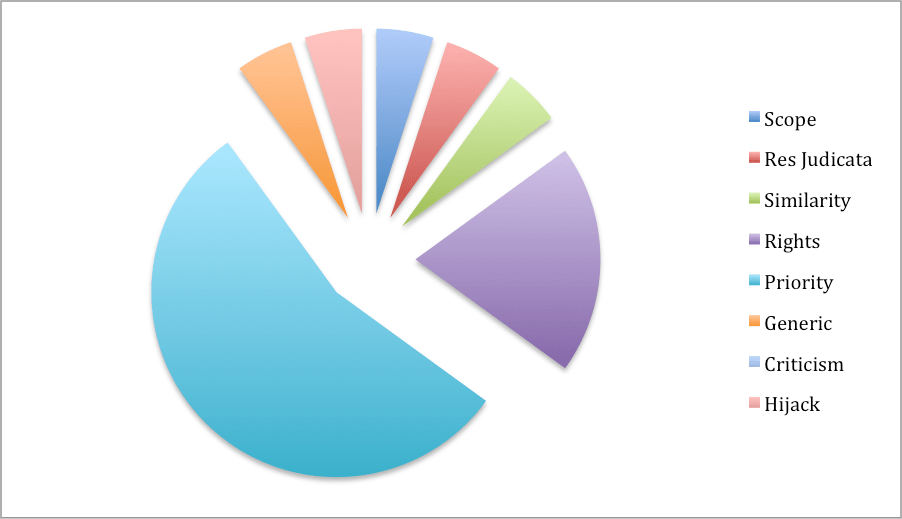

We analyzed each victory for a respondent based on the grounds cited by the UDRP panel. Many decisions had more than one ground cited, so the total count of issues exceeded the raw number of decisions. One decision was not available online, and so counts as a denial but does not have grounds coded.

As in 2016, far and away the two most common causes of complainant’s losses were a failure to show any trademark rights that predated the domain name registration date (40.1% of decisions) or a failure to adequately demonstrate any trademark rights at all, particularly where the applicant claimed common-law rights (often in a fairly descriptive mark) without significant evidence of sales and advertising (14.9% of decisions).

One decision in particular was interesting: Wendy Murdoch, LLC v. Romero, FA 1706433 (Nat. Arb. Forum Jan. 13, 2017) (declining to transfer effortlessrider.com). The complainant had a trademark registration for the mark EFFORTLESS RIDER predating the domain name registration date, and used the domain name for competitive horseback-riding services, using the complainant’s mark prominently on the website. The panel had no problem finding that the domain name was confusingly similar to the mark nor that the use was a bad faith attempt to “create confusion for commercial gain,” but found that the respondent’s conducting business under EFFORTLESS RIDER – the complainant’s mark – insulated it under the “rights or legitimate interests” tab since the respondent was a “real business which offers real services” with an LLC of the same name (albeit created after the domain name was registered) and so was “commonly known by the at-issue domain name.”

This is a fairly perverse result. Under the logic, a seller of counterfeit Nike products that brands its entire site NIKE at the domain name nikeshoes4u.com would be immune to a UDRP, while a seller of counterfeit Nike products at a site titled SHOES at the domain name nikeshoes4u.com would, and so would a page of ads for NIKE knockoffs at the same domain. The first example is engaging in more conduct that the panel found to be bad faith, and which is explicitly conduct “for the purpose of disrupting the business of a competitor,” UDRP Par. 4(b)(iii), yet somehow creates a “right or legitimate interest.” Most panel decisions deal with the issue by noting that the domain registrant that uses “the domain name (and Complainant’s mark) to sell products in competition with Complainant demonstrates neither a bona fide offering of goods or services nor a legitimate noncommercial or fair use of the name.” Ultimate Elecs., Inc. v. Nichols, FA 195683 (Nat. Arb. Forum Oct. 27, 2003). The “commonly known as” exception usually to domain owners who use the domain for goods or services that are unrelated to the goods and services provided under the trademark owner’s prior mark. The Wendy Murdoch decision appears to be incorrect, and, if the line of reasoning spreads, potentially problematic for complainants, who will need to use the ACPA or another slower, more expensive enforcement option.

The new symbol:

The new symbol: