Rembrandt’s 1632 oil painting “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp”

What is “Anatomy of an Office Action Response”?

We are starting a new series of blog posts called “Anatomy of an Office Action Response.” In this series, we will do a deep dive into a recently-filed, successful trademark Office Action Response: the mechanics of filing, strategic considerations, and the arguments that won the day.

The Office Action – PRIVACYCORE

Today, we are looking at a successful response to an Office Action for the mark PRIVACYCORE in the stylized format shown below, Ser. No. 86/922,696. The Examining Attorney viewed and initially searched the mark as EPRIVACYCORE; more on that later on.

Mark:

Register: Principal

Class 41 (original ID): Training services in the fields of privacy and data security; e-learning services, namely, providing online training courses and training materials in the fields of privacy and data security; providing an electronic library of training courses and training materials in the fields of privacy and data security for delivery by means of a learning management system (LMS)

Applicant: The International Association of Privacy Professionals, Inc.

Filed: Feb. 29, 2016.

In the initial Office Action, the US Patent & Trademark Office Examining Attorney preliminarily refused registration under Section 2(d) of the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. §1052(d), on the basis of a likelihood of confusion with Reg. No. 4,919,881.

Mark: EPRIVACY OFFICER (disclaims “officer”)

Register: Supplemental

Class 45: Consulting and legal services in the field of privacy and security laws, regulations, and requirements

Registrant: Nanette Awad

Filed: Jul. 29, 2015

Registered: Mar. 15, 2016 (Supp. Reg. date Jan. 10, 2016)

The Office Action focused on the relationship between the fields of use (training vs. consulting services in the same privacy and security fields) and the similar starts of the mark, EPRIVACY—.

The Office Action also noted a potential likelihood of confusion with two prior pending applications, Serial Nos. 79/177,839 (TRADECORE) and 86/683,357 (EPRIVACY HEALTH SOLUTIONS). Details for each follow:

Mark: EPRIVACY HEALTH SOLUTIONS

Register: Principal

Applicant: Nanette Awad

Filed: Jul. 5, 2015

Abandoned: May 24, 2016

Mark: TRADECORE

Register: Principal

Registrant: Onventis GmbH

Filed: Sep. 8, 2015

Reg.: Oct. 11, 2016

Class 9: Computer software for electronic data processing in the field of cloud-based procurement and electronic procurement processes

Class 35: Organisational business project management in the field of electronic data processing; updating and maintenance of data in computer databases

Class 38: Providing user access to global computer networks

Class 41: Arranging of seminars; conducting of seminars in the field of procurement processes, ecommerce, and supplier-relationship management; training services in the field of procurement processes, ecommerce, and supplier-relationship management

Class 42: (a long mix of data security focused software and services)

The Office also suggested some minor amendments to the descriptions of services. None of the changes were substantive nor affected the substantive portions of the response, and we will not focus on them for the rest of this post.

Analyzing the Office Action

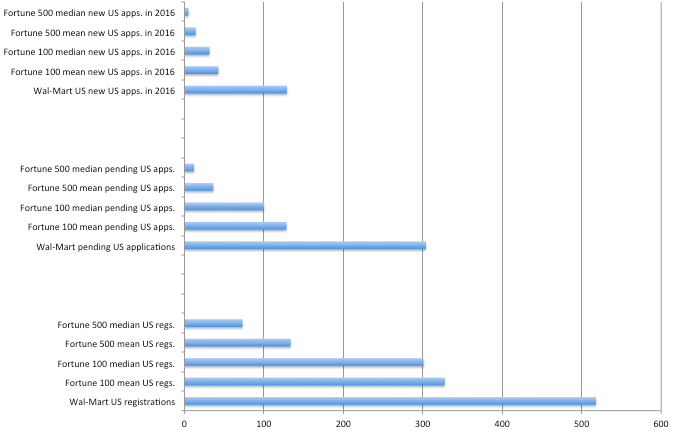

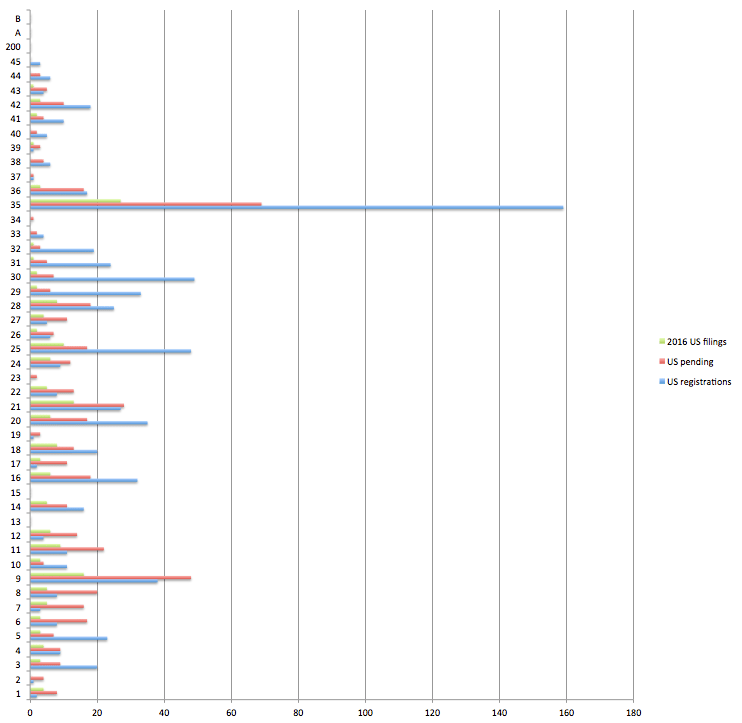

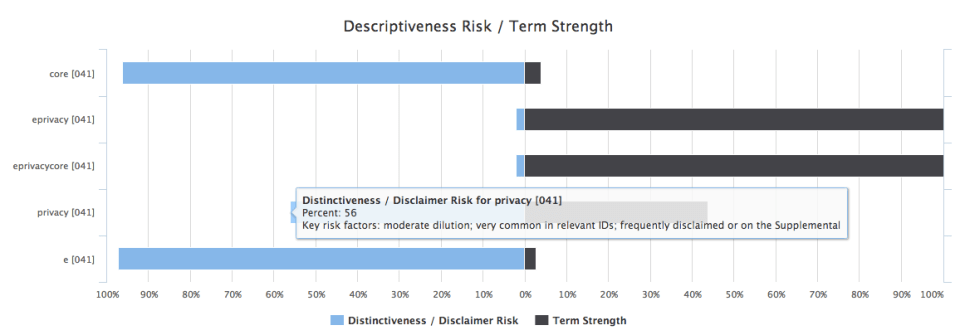

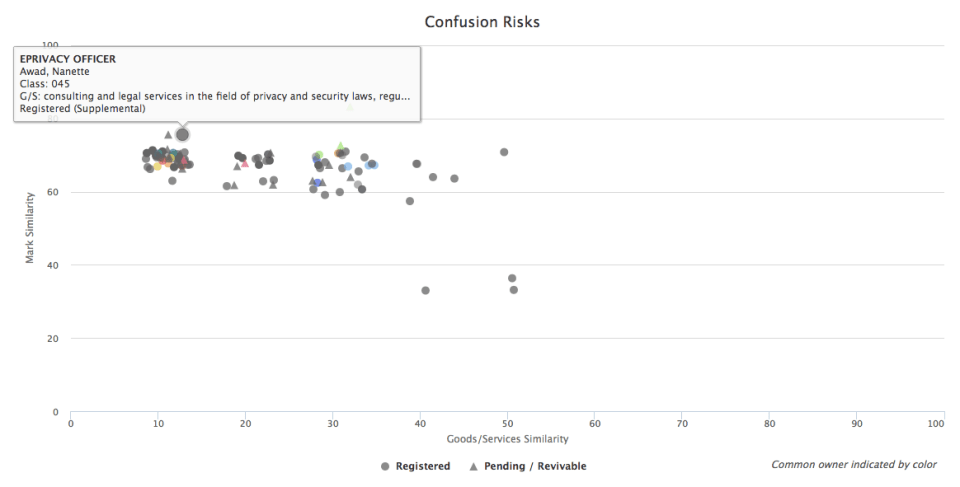

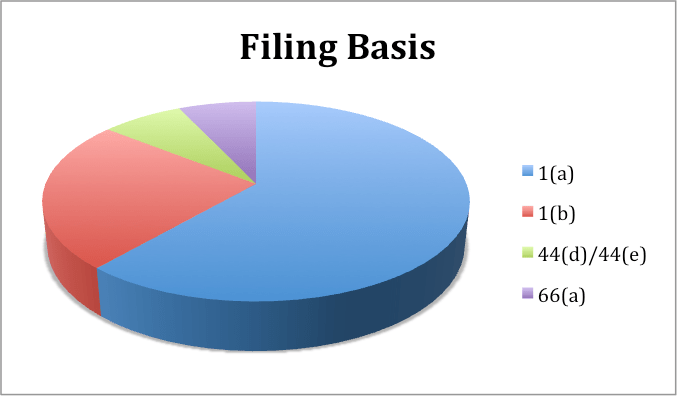

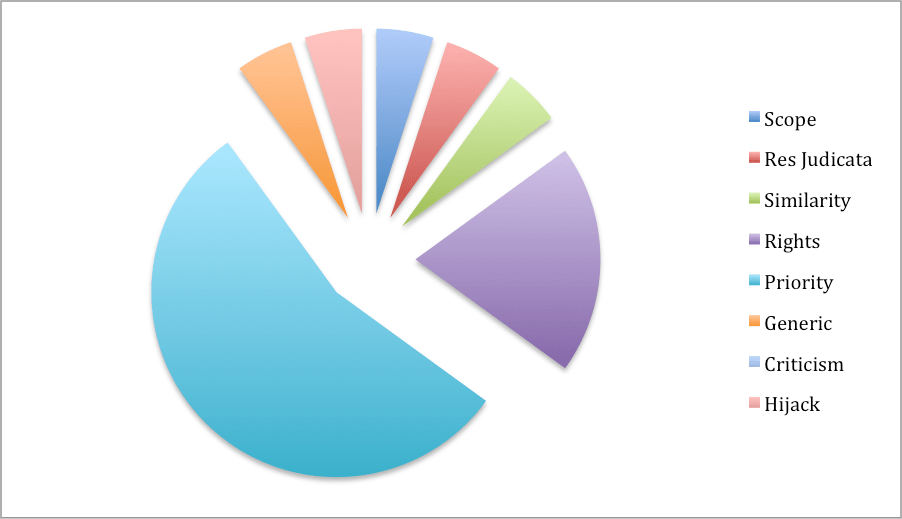

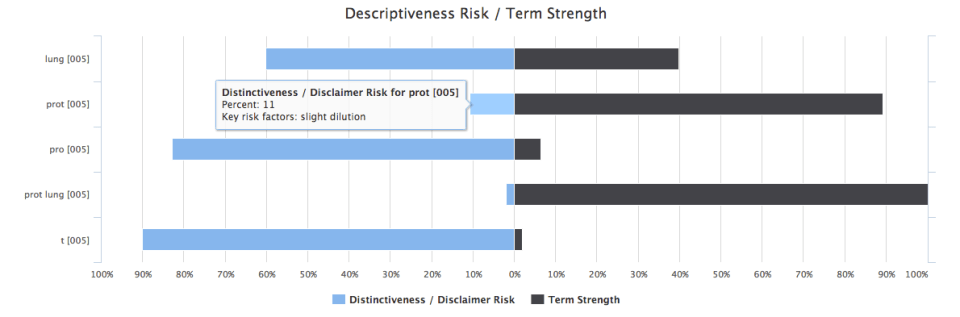

We will do a quick analysis of the Office Action through the prism of TM TKO’s tools. You can see an interactive version of a search report for EPRIVACYCORE (searched with an initial “e,” as the Examining Attorney did) here.

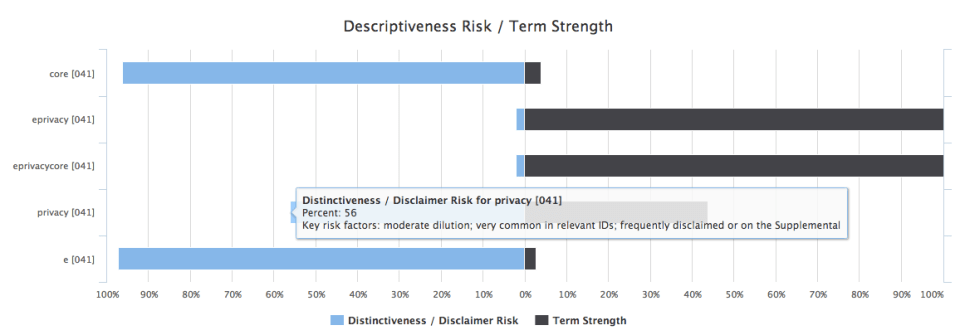

This bar graph shows how TM TKO divides up the mark (E – PRIVACY – CORE) and the relative distinctiveness of each of the terms in the mark (none very distinctive on their own). For example, “privacy” in Class 41 is commonly disclaimed and moderately diluted on the registry, and shows up frequently in relevant descriptions of services. The “e” prefix and “core” each also appear relatively weak.

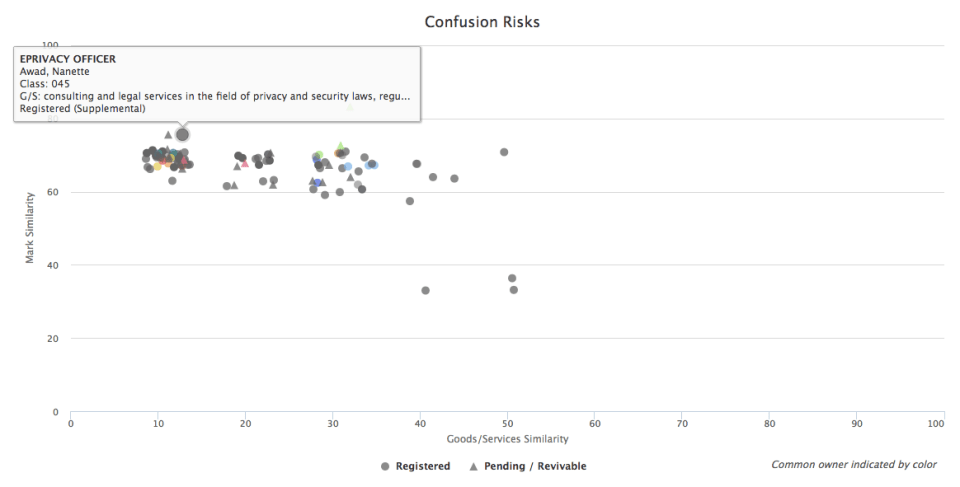

Plotting out mark similarity, with mark similarity on the vertical axis and goods/services similarity on the horizontal axis, the registration for EPRIVACY HEALTH SOLUTIONS scores out as the most similar mark, though it is out of class and on the Supplemental Register.

The strategy for addressing both of the prior cited marks that had not gone abandoned at the time of the response seems pretty clear: argue that the differences between the marks outweigh the similarities, and that shared portions of the mark aren’t strongly source indicating by themselves, as in Citigroup Inc. v. Capital City Bank Group, Inc., 98 USPQ2d 1253, 1261 (Fed. Cir. 2011) (no confusion likely between CAPITAL CITY BANK and CITIBANK due to commonality of “City Bank” in the industry).

The Office Action Response

Counsel for the applicant, Wade Savoy of Patent GC, argued that confusion was unlikely to occur with either of the two still-active cited registrations.

For the EPRIVACY OFFICER citation, the applicant argued that the applied-for mark was in fact just PRIVACYCORE not EPRIVACYCORE, and that the initial design is abstract rather than a design of an “e.” The applicant pointed to its textual uses of PRIVACY CORE, where the mark did not include an “e,” as evidence. This is a reasonable argument, and perhaps the only one the applicant can make: the actual use of the mark does significantly impact how customers and the public are likely to perceive the mark. It does not seem like current use is entirely determinative, though. First, the applicant could be using two very similar marks, and consumers could see them as distinct. Second, and maybe more importantly, the applicant’s use of a related mark could change, and the applicant could change to EPRIVACYCORE without impacting the existing registry. In any event, the argument was apparently accepted; the mark remains identified on the registry at publication as PRIVACYCORE with no initial “e.” The remainder of the applicant’s argument – that the shared term PRIVACY was far outweighed by the differences between CORE and OFFICER – was, naturally, quickly accepted. It is far from clear that the refusal would have “stuck” even if the mark was viewed as EPRIVACYCORE, but the applicant would certainly have had a more difficult road.

For the TRADECORE prior filing, the applicant emphasized the differences in the marks, especially their first terms, TRADE vs. PRIVACY, the distinctions between the training services each offer (information privacy vs. ecommerce supply information), and the differences in trade channels and customers implied by the different training service areas. While the prior filing also included the broad “arranging of seminars” without limitation and technically the overlap between the two filings is fairly strong, the practical differences in the marketplace paired with the differences between the marks won the day.

Stylistically, the applicant kept the reply fairly informal, referring to all the relevant precepts of trademark law but without citations or highly technical arguments. This is frequently an effective style, and was a great fit here for two reasons. First, the arguments that the mark is likely to be perceived as PRIVACYCORE instead of EPRIVACYCORE is not fundamentally rooted in case law, and finding directly on-point cases would have likely been a time-consuming and expensive process for minimal benefit. Second, neither of the marks that generated the 2(d) citations were that similar. Exhaustively citing cases for basic propositions of law, like the main DuPont factors argued in the response, would have been overkill, and there were no highly technical arguments required that would have benefitted from detailed case law citations. There may also be some benefit from not making a weaker refusal “feel” stronger by making extensively arguments – or at least from not making the Examining Attorney plod through a twenty page document when a couple of pages will make the same point just as well.

TL;DR

It is sometimes easier to correct the assumptions underlying a refusal than to fight it out on each point of law.

We hope you like this series and find something informative in each “Anatomy of an Office Action Response” post.

The new symbol:

The new symbol:

Every week, TM TKO will look at a major company and its trademark portfolio.

Every week, TM TKO will look at a major company and its trademark portfolio.