For the past two weeks, TM TKO ran a survey about how trademark professionals are feeling about their practice in 2020. We’ll summarize the results in this blog post. Thanks to our users and to participants on Oppendhal Patent Law Firm’s e-trademarks listserv for their responses!

About TM TKO

A very quick word about us – TM TKO has been providing daily or subscription-based access to a variety of trademark research tools since 2015. Our customers include AmLaw 100 firms, trademark boutiques, solo practitioners, government agencies, in-house counsel, and more. We had our best year ever in 2019, and are looking forward to 2020.

We aim to help trademark lawyers with three main pillars of all successful trademark practices: solving everyday problems, solving hard problems, and growing practices.

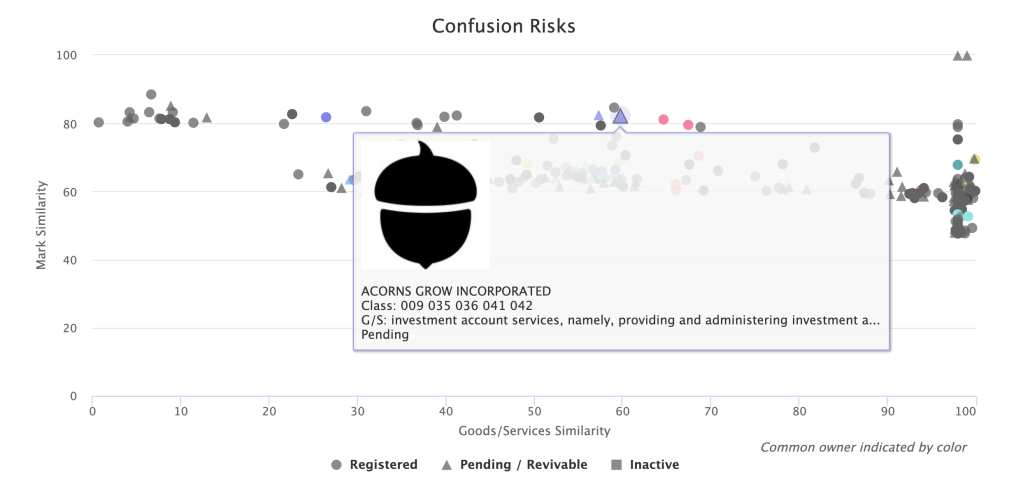

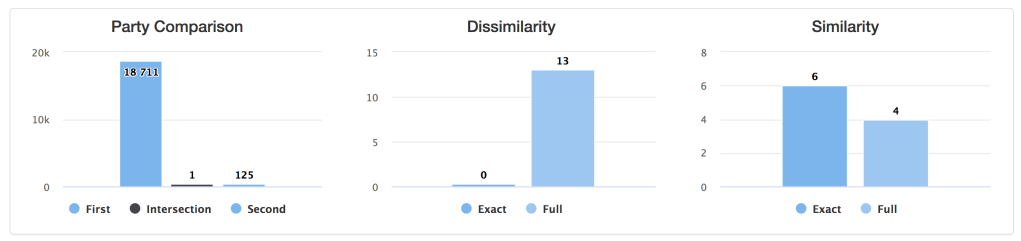

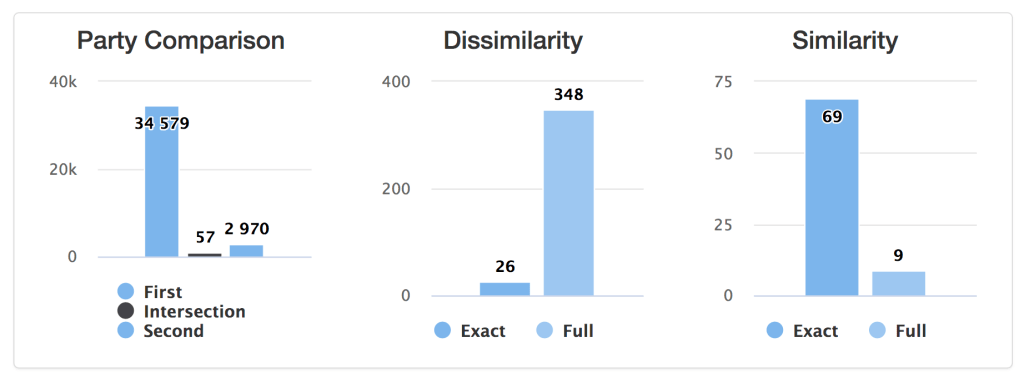

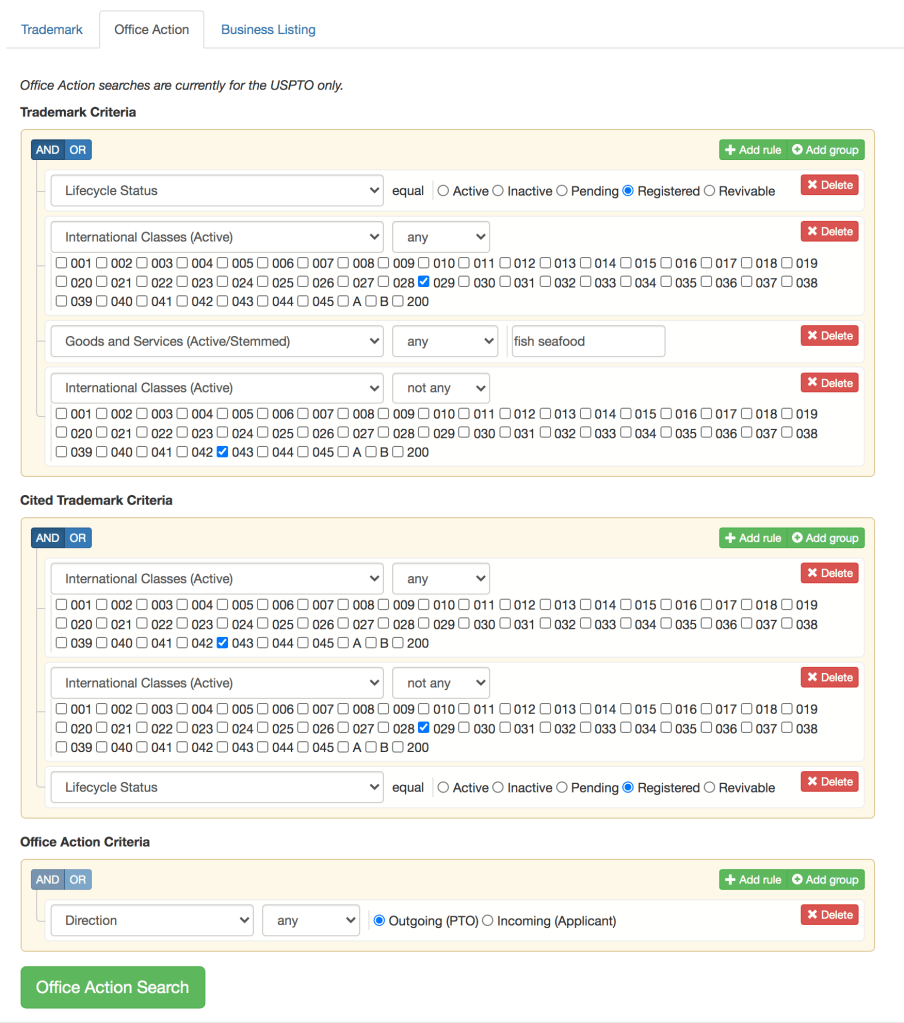

Everyday problems: our clearance, search, and watch tools help you with your day-to-day practice needs. Hard problems: specialized research tools like trademark Examiner analytics, automated and manual Office Action research, and comparative research via ThorCheck® can help overcome difficult prosecution refusals. Growing your practice: we have an expanding set of marketing solutions to help grow your client base and generate more projects for existing clients.

Haven’t used TM TKO yet? It’s free to try for 30 days.

To the Results!

Trademark Practice – Size and Geography

50% of respondents practice in groups of 2 to 5 trademark lawyers; the rest were evenly split between solo practitioners and larger groups.

Almost half of respondents were from the east coast, with about 20% each from the west coast and southeast, and a smattering elsewhere. All but a couple of respondents were American lawyers. Of those, about 70% were in large cities, with the rest in small-to-medium size cities.

Expectations for 2020

People felt pretty good about their personal practices and about their firms’ trademark practices – just above 50% felt like their personal practice was improving and 40% felt their firm’s trademark practice was improving (respondents were high achievers, apparently). About 40% expected a similar year, and under 10% expected a worse year or couldn’t guess how the year would go.

US prosecution work was the main growth area for 66% of respondents, with smaller numbers seeing growth in international prosecution, non-litigation disputes, and prosecution. Litigation was a growth area for only 15% of respondents, and a slowing practice area for 20%.

Client relationships remain key – 63% of respondents generate most of their new work from existing clients; domestic referrals are a key for 45% of respondents and international referrals from foreign counsel for 28% of respondents. Respondents’ own business development efforts were only a significant factor for 25% of respondents.

The low level of direct business development efforts maybe isn’t a good thing, though; 45% of respondents listed client acquisition as their single biggest challenge for 2020. Staffing, price pressures and commoditization, technology, and practice costs all had over 20% of respondents worried. Two things generated lower levels of worry: clients paying (17%) and client retention (11%). Once clients are in the door, they tend to both pay their bills and stick around.

Technology

A lot of lawyers changed some of the technology tools that they use for practice in 2019, but seem less inclined to do so in 2020. Search, watch, research, prosecution research, and docketing tools all polled over 25% for 2019; only other research tools (over 50%) cracked the 20% mark for 2020. Respondents were generally enthused about technology improving their practice and its efficiency, although there several respondents comments on technology-adjacent concerns about filing mills and unauthorized practice of law rules.

The USPTO and Its Performance

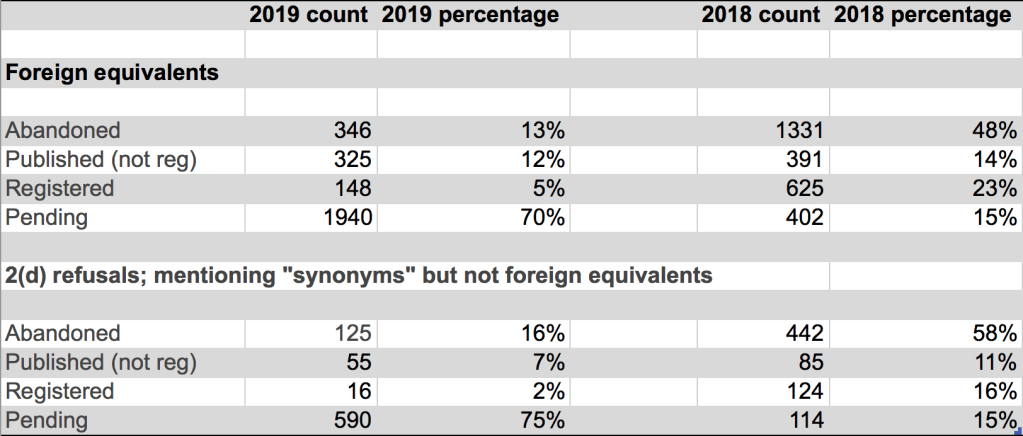

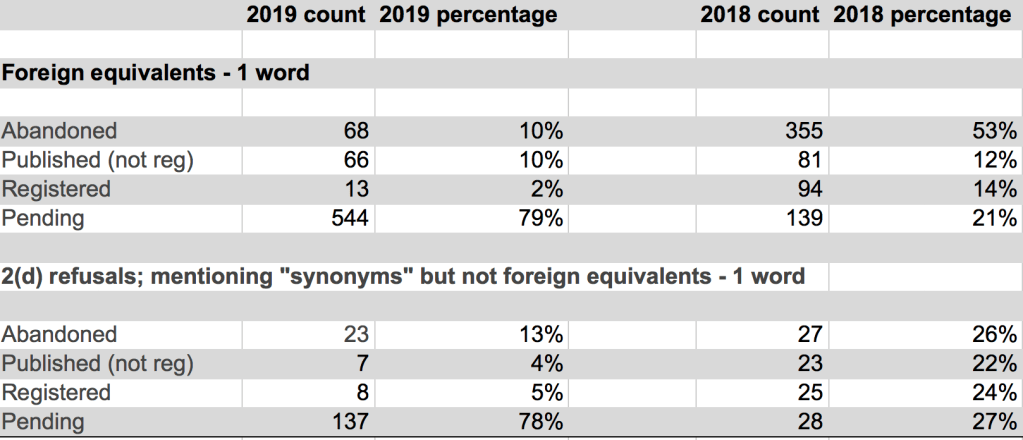

The good feelings end here. 62% of respondents think the USPTO is doing a worse or much worse job in examination than in recent years, and only one respondent thought it was improving. 66% of respondents said that the USPTO has gotten better at nothing in the last several years; about 20% commended the USPTO on changes for website usability and 10% on improved TTAB decisions. The most common gripes: 40% took issue with examination on 2(d) issues, 30% on 2(e) issues, 45% with website usability, and 45% other prosecution issues. 17% felt there were no negative changes and 10% found that TTAB decisions were getting worse.

The “disastrous implementation” of the domicile and email rules was specifically called out by a number of respondents, as were specimen issues and the problems the USPTO is having keeping the registry clean of marginal use claims (and its spillover onto legitimate applicants).

Travel, Education, and Networking

75% of respondents usually attend the INTA Annual Meeting, by far the most of any meeting. 40% go to an unlisted event, with 20% or fewer going to the INTA Leadership Meeting, the AIPLA Annual Meeting, a state bar annual meeting, or the ABA IP Bar annual meeting.

This year, the travel to Singapore appears to be really hitting INTA attendance, at least among the North American lawyers who responded to this survey. Only 31% said they were attending this year (a 40% drop); anecdotally, people suggested that the costs and travel time commitments are the main reasons for this decision. TM TKO is in this group, too – we are allocating our time and conference budget elsewhere this year. One wonders if potential late-attendee numbers might drop as well, due to the outbreak of the coronavirus in the region. Other conferences had roughly similar numbers.

Conclusion

We hope your trademark practice has a great 2020, and if TM TKO can do anything to help make that a reality, don’t hesitate to contact us.